![]()

From The Dallas Times Herald

Jan 3, 1985

LOS ANGELES – Louie Anderson heard his name and knew it was time to move toward the light. There was no more time to worry, no more time to dream. There was only time to straighten his tie and swallow hard, to catch a glimpse of the stagehand who was holding the gray curtain open, who was gesturing for him to go ahead.

He walked through the curtain, looked briefly to his right and smiled at the scene that was just as he’d always hoped it would be. There was Johnny Carson, behind his famous desk, in front of his famous Hollywood backdrop, smiling and clapping his hands. Robert Blake, dressed in black and fingering an unlit cigarette, was in the guest’s chair. And, yes, on the sofa. There was Ed McMahon, clapping along.

Louie found his mark, two pieces of green tape stuck to the floor in the shape of a T, and positioned himself in front of the camera. To his left, Dock Severinsen was giving the signal to end the music, the generic brassy music they use for every new comedian. This time though, the music sounded different to Louie Anderson. This time the music was for him.

“I could work for the rest of my life touring in clubs and tomorrow night more people will see me than in all of those clubs put together,” Louie had said the day before. “This is what every comic dreams of. It changes everything because for the rest of your life, wherever you go, they say, “As seen on “The Tonight Show.”’

“Not many people get a chance like this – one night that can change their whole life.”

**************************************************

The amateurs were everywhere, tables full of people who thought they were funny, waiting for their shot at making strangers laugh.

It was another take-your-chances Monday night at The Comedy Store, the legendary comedians’ proving ground on Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard. Monday is open microphone night, which means anyone who wants to make a fool of himself in public need only take a number and wait in line.

Most of the applicants were crowded in a back corner, a huddled mass of wretched comedy refuse, laughing at one another’s jokes, the only ones laughing in the room. Some of it was painful to watch, feeble attempts at being funny.

They would go to the stage, one after another, always moving too fast, always fumbling with the mic, trying to get one laugh before their three minutes expired. One guy showed up with a 2-by-4 and said things like, “I found this at a board meeting.” One was doing Mary Jo Kopechne jokes. Another simply froze and uttered not a single intelligible word. He just stood there muttering, waiting for the light to shine on Eddie Cantor’s portrait, the signal that his time was up.

It was an endless parade of half-wits and loudmouths, guys (and they were all guys) who thought they could get laughs just by saying dirty words and making faces. If, by some incredible accident, one of them uttered a line that was even remotely humorous the crowd would go crazy. Mercy laughs.

But mixed among the pitiful amateurs there are always a few people who know what they’re dong, young comics who have come from other places, ready to take their shot at the big time. If you’re going to make it as a comedian, this is where you have to start: taking a number and standing in line on Monday night at The Comedy Store.

That’s what Louie Anderson did. He came to L.A. in September, 1982, four years after he had taken a dare and gone onstage at a comedy club in Minneapolis, a cramped working-class bar called Mickey Finn’s. He was a social worker at the time, a kid who’d grown up dirt poor in a St. Paul housing project.

Louie was funny and he knew it, a 350-pound guy who could make fun of himself and everything around him. He was a hit the first time he took the microphone and it wasn’t long before he left social work behind. Deep down, he says, a comedian is what he’d always wanted to be.

After accomplishing all he could in Minneapolis, he took off for California. He planned to stay a year and then, if he hadn’t gotten on “The Tonight Show,” he’d go back to Minnesota. A year passed. He didn’t get on. He stayed anyway.

He’d become a paid regular at The Comedy Store by February, 1983, only six months after his arrival. He’d even gotten an early audition for Jim McCawley, “The Tonight Show’s” talent coordinator. But McCawley turned him down, said he wasn’t ready. Louie swore he’d never audition for the show again.

“I was devastated,” he said. “I’d been rejected and I took it very personally. I’m immature. I think comics are immature people.”

A few months later, abandoning his promise, Louie auditioned again. And he was turned down again. By then, though, he was getting plenty of work in comedy clubs on the West Coast and working as an opening act in Las Vegas for acts such as Neil Sedaka and Connie Stevens. So he stuck it out.

Finally McCawley came through. He called Louie back for one more audition in mid-November and decided he was good enough.

“You’re gonna get your shot,” he told Louie. “We’ll put you on in the next three or four weeks. Unless someone cancels.”

Someone cancelled. The Friday after that conversation. Louie’s phone rang. It was McCawley.

“You’re doing it Tuesday.” He said. “This Tuesday.”

Louie calmly went over the specifics. He’d have seven minutes and would go on after Robert Blake. Fine, he said to McCawley, thank you very much. He then proceeded to call every human being he could think of.

“ I don’t care if I haven’t talked to you in three years,” he said to one long-distance friend. “Watch the show.”

He spent the weekend honing his set, working on the lines McCawley had liked, taping his club performances and playing them back against a stopwatch.

And now it was Monday night, the night before the big show and he was back at The Comedy Store, in the midst of all the amateurs, so he could try out his “Tonight Show” set for one last audience. A final dry run.

While he was waiting to go on, every comic in the back hallway was asking questions and giving advice. “Is Johnny gonna be there?” “Do you get to sit down?” “What are you gonna wear””

He was loving every second of it, basking in the glory, hamming it up, trying to pretend he wasn’t nervous and doing an awful job.

“Do you think I need a haircut?” he asked. It was 11 p.m. “If you don’t feel good about your hair it makes a difference. I better get one tonight. If I can find the woman who cuts it for me, will you drive me over there? Great.”

He did his set twice that night, the same jokes in the same order he would do them for Carson and 18 million viewers in less than 24 hours.

“Sorry, I can’t stay long,” he said as he walked on stage. “But I’m in between meals.

Small laughs. Very small. He was hurrying too much, rushing the punch lines, forgetting jokes. The lines were good but his delivery was not. What had been a meticulously-timed seven-minute routine clocked in at under five.

“I went shopping today,” he said. “What’s this one-size-fits-all stuff?”

“Terrible crowd,” he said, as he headed backstage.

He decided it was too late for the haircut and instead end up gong to Cantor’s Delicatessen, a comedians’ hangout.

“What time is it,” he asked after he’d ordered a Reuben sandwich.

“12:15,” he was told.

“I’m gonna be on the “The Tonight Show” tonight.”

**********************************************************

**********************************************************

Louie lives in a one-bedroom apartment in North Hollywood, a town that is separated from the real Hollywood by hills, canyons and money. There is no glamour in North Hollywood. Louie’s neighborhood is an ugly sprawling mass of prefab apartment buildings, construction supply warehouses and fast-food restaurants.

But it’s cheap and it’s convenient. A working comic’s dream.

Louie’s apartment – the walls covered in greenish sheet rock, the bathroom cabinets stuffed with hotel towels – is crowded with comedy paraphernalia. There are old movie posters, ventriloquist dummies, a shelf full of props. The desk in the living room is covered with 8-by-10 promo shots of Louie, the paneling above the kitchen decorated with pictures of him arm in arm with assorted celebrities – Henny Youngman, Robin Williams, Mr. T and Ray Charles.”

“That’s a good one, “ Louie says. “He thought it was Gleason.”

But Louie does most of his work from his bed. He’s surrounded himself with everything he needs, telephones, answering machines, tape recorders, book shelves. He stays in there for hours at a time. The day of his “Tonight Show” appearance he stayed in there until nearly 2 p.m.

Friends called. Telegrams arrived. Louie wandered into the shower and stayed there for almost an hour, listening to Prince’s “Purple Rain” soundtrack over and over.

“Last night before I went to sleep, I went through the set in my head,” he said, finally emerging from the bathroom only an hour before he was supposed to be at the studio. “I also had this dream that every bad thing I ever did in my life, Johnny had a list of it.

He seemed jumpy, a little disoriented. He couldn’t find his socks. He said he was fine.

“I’m not nervous,” he said. “I’m excited.”

The taping didn’t start until 5:30 p.m., but Louie wanted to get to NBC’s Burbank Studios, a half hour away, by 4.

“I want to get there early,” he said, “so I can see where I’m supposed to stand.”

After the show Louie would have to go directly to the Burbank and catch a flight to Las Vegas where he and some other Comedy Store regulars were appearing at the Dunes Hotel. So now there was a mad rush to pack his bags, to get everybody in their cars and caravan over to NBC.

The back-entrance security guards found his name on the list and waved the whole gang through, pointing out the proper parking area, very near Johnny’s sparkling white Corvette. Everybody was piling out when Louie made a horrible sound.

“Oh, God,” he said. “I’ve left my suit at the apartment. The one I was going to wear on the show.”

He wasn’t nervous. Just excited.

One carload of comedians went to retrieve it while Louie found his dressing room, a small paneled cubicle with a dressing table and a plaid sofa, a TV monitor, a coffee table and a bathroom.

“Who was in here for the last show?,” some asked the security guard.

“Lee Meriweather I think.”

Louie’s name was printed on a star that was fastened to the door and decorated with “The Tonight Show” logo. “I’m gonna save that, “ he said.

He asked the guard if he could walk onto the set. “You’re the boss, tonight,” he was told. Louie wandered past the curtains into the empty studio.

“This is it, “ he said, looking up at the 500 blue seats, turning to take in Johnny’s desk, the couch, the cameras, the bandstand. “This is history.

He walked to Carson’s star, the place where he stands to deliver his monologues, and stood there for a while, not saying anything.

By 4:45, the guys were back with the suit and the tiny dressing room was filling up with friends, most of them nervously chewing on vending machine pretzels.

“Nice place,” one of them said. “Think we out to knock on the door and see if Robert Blake’s in there?”

“No!,” Louie blurted. “Don’t do that. Don’t start acting like jerks.”

Then he went to the bathroom.

Comedians kept showing up, Comedy Store regulars who’d done “The Tonight Show” themselves and were there to help Louie through his first time, sort of like a comedy support group.

“Louie, it’s an easy room,” said Bill Maher, a young comic who’d done the Carson show a dozen times and who had just signed to star in his own sitcom. “It’s the easiest room you’ll ever play.

Louie nodded, made casual conversation, went back to the bathroom.

“You won’t sit down unless you go long, “ Maher told him. “If you go long they can’t bring out the third guest and you get a freebie sit.”

Louie was looking in the mirror. “I’m glad I didn’t cut my hair,” he said. “It looks just right.”

At 5:30, as the show started, they tried to turn on the monitor but couldn’t figure out how to get it to work. The monologue was over before the picture came on. Johnny and Ed were on the couch by then, doing a bit about McDonald’s selling it’s 50 billionth hamburger.

“Ohhhh,” Louie said. “That should be my opening joke.”

“Just wait, “ Maher told him. “Listen to this. You don’t want to step on his routine.”

Carson was rattling off statistics about McDonald’s using 435 cows worth of beef a day and 32,000 pounds of pickles.

“I should walk out there and say I was just at McDonald’s,” Louie said,” and all those statistics have changed.”

“Don’t do it,” Maher warned. “Stick to the script your first time.”

“You’re right,” Louie said. And then he went to the bathroom.

It was 6 pm when the knock came. It was McCawley, the talent coordinator, ready to escort Louie to the backstage area. After the next commercial, Louie was on. They went down the back hallway together, turned right and disappeared behind the curtains.

The pack of comedians made a mad dash through the green room (which isn’t green at all) almost trampling Selma Diamond, who was to be the show’s third guest. They were headed for the tunnel, the area behind the main camera, a place where they could watch Louie live, without a monitor, without having to peek through a curtain.

The commercial ended. Carson put out the cigarette he’d been smoking while he was talking to Robert Blake off camera. The spotlights were trained on the gray curtain, the stage hand standing behind it, out of sight.

And now,” Johnny Carson said, “Will you welcome, please, Louie Anderson.”

This time the music was for him.

***********************************************

“I can’t stay long,” Louie said, coolly scanning the crowd as the music faded. “I’m in between meals.”

It was like an explosion. The laughter rolled down like a wave. And it was just his opening joke. Maher had been right. The easiest room he would ever work. Louie took the chance.

“I just got back form McDonalds,” he said. Maher winced. The whole pack of comedians, by then nearly a dozen, held their breath. “And all those statistics have changed.”

Another roar. And Carson was bent over. Laughing.

“I’ve been trying to get into this California lifestyle,” Louie was saying, as calm as he could be. “I went to the beach the other day but every time I’d lay down, people would push me back into the water.”

Every joke was perfectly timed, every punch line smoothly delivered. Louie did double takes. He waited for the applause, which came often. They were in the palm of his hand. He had a series of jokes about trying out for the Olympics, about how he drove the pole vault into the ground and straightened out the uneven parallel bars and, here it comes, the big one.

“Broad jump?” He waited for the beat. One. Two. Three. “Killed her.”

Another roar. Carson, the master himself, was pounding on his desk he was laughing so hard. Louie had scored beyond his wildest expectations. It was a fairy tale.

The last joke was followed by a thunderous ovation that Louie acknowledged like a heavyweight fighter who’d just delivered a knockout punch. He turned, finally, and went back through the gray curtain. But the applause didn’t stop.

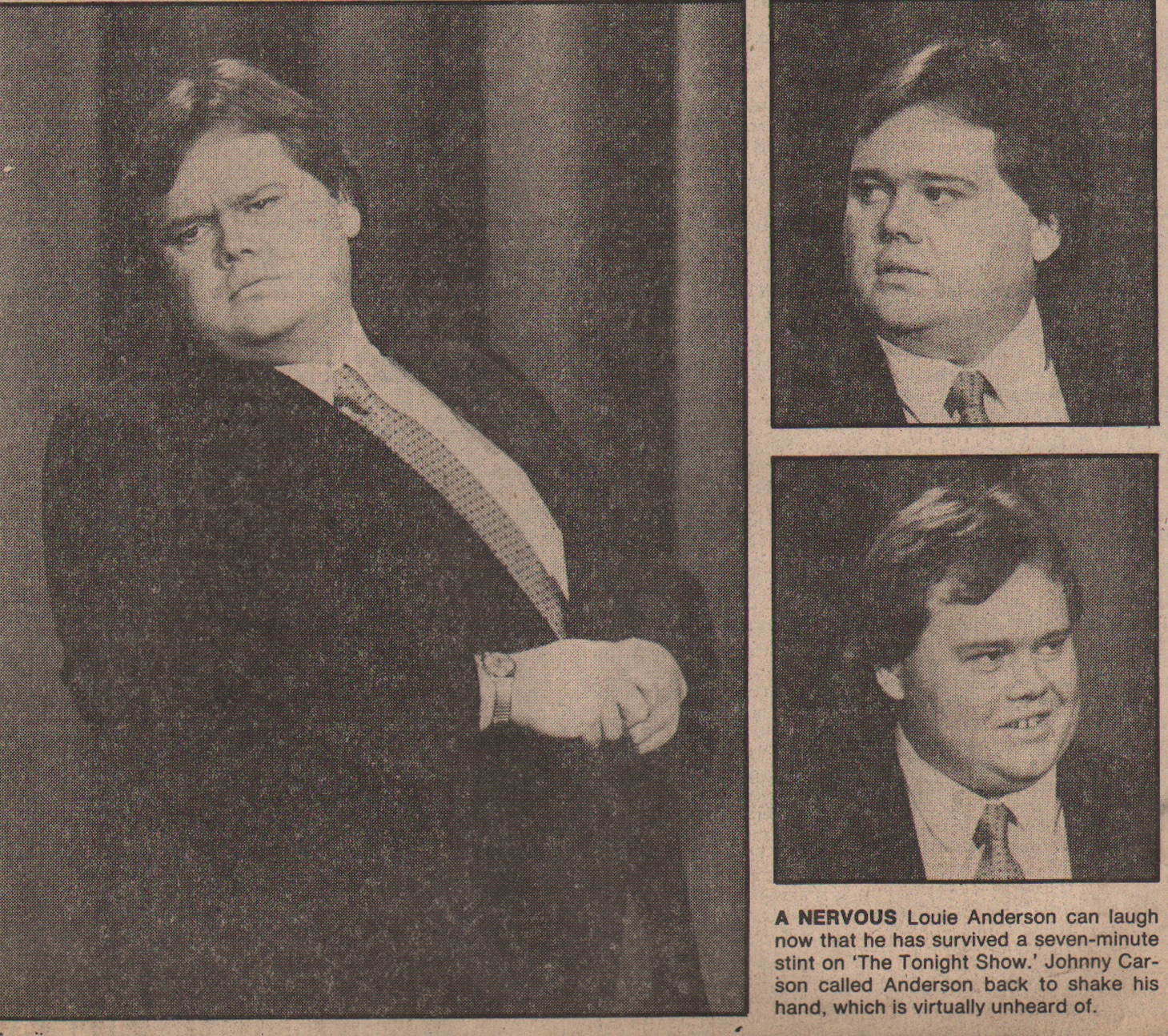

And then, something that never happens, Carson called him back for another ovation and went over to shake Louie’s hand.

“Did you see that?,” one of the comics gasped. “Johnny never comes over like that. That’s as good as it gets.”

Louie took the extended hand and leaned forward, whispering into his idol’s ear.

“Thank you, “ he told him, “for making a dream come true.”

After the show, the dressing room was like a World series locker room, all backslaps and war whoops. It all went too fast. There was Peter LaScally, the show’s director coming back to tell Louie that Johnny wanted him to do some concert dates with him. And then, the man himself.

“Helluva good spot,” Carson said. “You were funny as hell. I’ll have you back whenever you want.”

Louie went to the bathroom.

There was not much time for parking lot euphoria. There was that plane to catch for Vegas. But Louie’s life had changed. All in seven minutes. He was 31 years old and he knew nothing would ever be the same again.

Carson left in his white Corvette. McMahon took a limo. And finally, Doc Severinsen wandered into the parking lot.

“Hot stuff, Louie,” he said. “A beautiful set.

Louie Anderson said something about his dad, how he was a trumpet player, too. He blurted it out, just something to say, anything. The night suddenly felt so unreal, too much like the dream he’d had for so long.

“See you soon,” Severinsen said, climbing into his car. “Undoubtedly see you soon.”