So, where were we? Oh yeah, Vermont, at the Sanctuary on Blueberry Lake.

I headed west from there, the beginning of a slow drift back towards Texas. There were just enough nights with temperatures in the 30’s to serve as reminder that I’d eventually have to head south. But I took the long way home.

It was jarring how much the world changed as soon as I crossed out of Vermont on U.S. Highway 4 and into upstate New York. East of the state line, the people and the countryside felt mellow and relaxed, a little New England and a little New Age. But as soon as I crossed into New York, heading into Glens Falls, it’s like the real world, recession-scarred and gloomy, had returned. The people seemed less welcoming, the towns full of junkyards and dive bars. Suddenly I’d entered a more blue-collar, rust-worn world; grimier, beaten-down. Vermont felt like a haven, New York like a harbinger of harder times to come.

It was jarring how much the world changed as soon as I crossed out of Vermont on U.S. Highway 4 and into upstate New York. East of the state line, the people and the countryside felt mellow and relaxed, a little New England and a little New Age. But as soon as I crossed into New York, heading into Glens Falls, it’s like the real world, recession-scarred and gloomy, had returned. The people seemed less welcoming, the towns full of junkyards and dive bars. Suddenly I’d entered a more blue-collar, rust-worn world; grimier, beaten-down. Vermont felt like a haven, New York like a harbinger of harder times to come.

The waitresses at the diners didn’t call me “Hon” anymore. They were brusque, distracted, less inclined to chat. That I was from somewhere else made me interesting in Vermont, someone to engage. In New York, I got the distinct impression they were wary of me, suspicious of strangers in general, and me in particular, a flannel-wearing weirdo in an ominous gray van. They wanted me to keep moving. And, because I’m a giver, I did.

Not that I didn’t enjoy myself. The back roads drive from Glens Falls to Syracuse, through Ithaca, past Cooperstown, over and around the finger lakes, was one of the most relaxing, beautiful days I’d had. I found a great pub in Syracuse, Riley’s, where the people at the bar , jammed elbow to rib cage, drinking beer and eating free happy-hour pizza, all knew each other. And there was drama in the dining room: a couple at the next table over, clearly breaking up. She was crying, quietly, trying not to make a scene, occasionally whispering, “Why?.” I couldn’t see his face, but he seemed to be nodding, occasionally trying to take her hand, which she instantly pulled away. Clearly, he’d picked this as the place to break-up, confident she wouldn’t dare break down in public, especially not during Happy Hour, or slap him in the face. It worked, I guess, in that they walked out together, kind of, her three feet ahead of him, still quiet, her eyes still wet with tears, her hand nowhere near his. Congratulations, sir. You’re a dick.

Me, I finished my lobster roll and multiple beers and stumbled down the hillside to the park, a half-block away, where the Traipsemobile was waiting. And that’s where I spent the night. The pavement was level, the street lights worked and that was enough for me. There may have been a few drug transactions in the park – clusters of hooded teenagers flitting in and out — and, I found out later, it wasn’t considered the safest neighborhood in Syracuse. But the Traipsemobile is its own best protection, particularly when the security system is armed and that little blue light is blinking in the windshield. No one’s going to mess with a vehicle like that, not the neighbors, not the potential thieves, probably not even the cops. It’s anonymous enough to blend in, intimidating enough to be left alone.

I thought, before this started, that finding a place to park overnight might be a challenge. But it hasn’t been at all, even in places where I know no one. I’ve parked in residential neighborhoods, municipal parking lots, at the Wal-Mart a time or two. As long as it’s level and there are other vehicles around, I’m comfortable spending the night. Maybe it’ll get harder when I head out West, when the towns are smaller and farther apart. But I don’t think so. And,, for some reason, I enjoy the idea of slipping unnoticed into a town, spending the night and then slipping away the next morning. Like I’m some sort of a ghost, invisible and anonymous, moving in and out of places and people’s lives without them knowing I’m there. Like The Shadow. Or the Dude. Maybe Sam Elliott, right now, is having a sasparailly in a bowling alley bar and talking about how he feels better just knowing I’m out there. Okay, maybe not.

I took the Southern Tier expressway around the base of Lake Erie and ended up in Beachwood, Ohio, near Shaker Heights the eastern suburbs of Cleveland, staying with a friend of mine, David Eden who was once my editor at the Dallas Times Herald where he once assigned me to “go to Los Angeles and look around. “ I ended up at the Chateau Marmont and, for some reason, hanging out with Harry Dean Stanton, who had no movies coming out but was willing to be interviewed anyway. I think that’s the same trip where I interviewed Bob Barker with his pants off, which didn’t weird me out me nearly as much as realizing I was staying in the same bungalow where John Belushi died. So, God bless David Eden for that.

He grew up in Cleveland, in this same suburb, and after years of being a big-shot in various places, came back home a few years ago, stirred up all manner of shitstorms at the local alternative weekly paper and then a television station and ended up teaching journalism for a year in the Arab Emirates. There’s going to be book about that. My suggested title would be, “Hey, Emir, would you like a schmear.” Cause, you know, he’s Jewish and all. No?

So now he’s divorced, back in his old neighborhood, — in a condo on Chagrin Blvd., which is a perfect Cleveland street name — not really sure what comes next. He showed me all around, took me to Corky & Lenny’s deli and Geraci’s pizza, the same places he used to hang out when he was a kid. He showed me gigantic mansions, which he says are on the market or a few hundred thousand dollars. That’s the thing. Pretty much everyone in Cleveland is broke. Or getting there. The place has more or less shut down. LeBron taking his talents to South Beach was just the latest proof that everyone who can afford to leave, has.

So now he’s divorced, back in his old neighborhood, — in a condo on Chagrin Blvd., which is a perfect Cleveland street name — not really sure what comes next. He showed me all around, took me to Corky & Lenny’s deli and Geraci’s pizza, the same places he used to hang out when he was a kid. He showed me gigantic mansions, which he says are on the market or a few hundred thousand dollars. That’s the thing. Pretty much everyone in Cleveland is broke. Or getting there. The place has more or less shut down. LeBron taking his talents to South Beach was just the latest proof that everyone who can afford to leave, has.

I took the RTA, nearly empty, into downtown Cleveland on a Monday afternoon to see the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and was practically the only pedestrian on the streets. It was spooky, like some sort of post apocalypse movie scene. There were lush green parks, beautifully landscaped, great old buildings – courthouses, city hall, — and almost no people. No traffic. I’m not sure exactly how neutron bombs are supposed to work, but this is how I always envisioned the aftermath.

It was, it turns out, a federal holiday and I was walking through a government office district, but, even so, let me repeat : THERE WAS NO ONE AROUND! Those Randy Newman lyrics kept echoing in my head . . “There’s an oil barge winding. . .down the Cuyahoga River . . .Rolling down to Cleveland, to the lake. Burn on, big river, burn on.” Pretty soon, I was singing them out loud. Which was fine. Because there wasn’t anyone to hear me.

Until I got to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which has become the only reason anyone ever goes to Cleveland. (Although, to be fair, there’s a giant decommissioned Great Lakes freighter, the William G. Mather, anchored next door at the Great Lake Science Center, which is pretty awesome.)

Until I got to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which has become the only reason anyone ever goes to Cleveland. (Although, to be fair, there’s a giant decommissioned Great Lakes freighter, the William G. Mather, anchored next door at the Great Lake Science Center, which is pretty awesome.)

The Hall of Fame is better than I expected, because what I expected was a big stinking love letter from Jann Wenner to himself , and there’s certainly some of that. And, sure, there are plenty of old guitars and Nehru jackets available for viewing at your friendly neighborhood Hard Rock Cafe But this is better. Just because there’s so much of it and it’s so well displayed. Letters and lyric sheets from Lennon, Elton John, Patti Smith. Exhibits about Sun Records and Elvis. Motown and Marvin Gaye. The old CBGB’s awning. The full stage set from Pink Floyd’s The Wall. Memos from Hunter S. Thompson. The table and notebooks on which Bruce Springsteen wrote. A lot of it is hokum. But a lot of it isn’t. It’s worth one visit. Not two. But definitely one.

And, as an added bonus attraction, Johnny Cash’s old tour bus was parked outside, available for walk-through tours. It’s mostly 70’s era technology, plush furniture, boxy tv monitors. I was happy to see that the Traipsemobile has a better toilet and a bigger tv. Johnny had a better bed though. And considerably better drugs.

And, as an added bonus attraction, Johnny Cash’s old tour bus was parked outside, available for walk-through tours. It’s mostly 70’s era technology, plush furniture, boxy tv monitors. I was happy to see that the Traipsemobile has a better toilet and a bigger tv. Johnny had a better bed though. And considerably better drugs.

I took the train back out to the suburbs (Best overheard passenger conversation: “What you been up to?” “Stayin out the way.”) and ended the nght at the Beachland Ballroom, in a mostly-abandoned part of town that they’re trying to re-invent as the Waterloo Arts District. It used to be the Croatian Liberty Home in the 1950s, but re-opened as a concert venue 10 years ago.

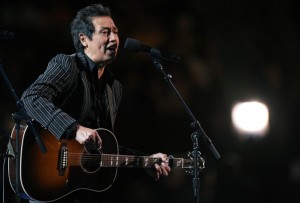

The people there that night to see Alejandro Escovedo – another Texan passing through – seemed to know each other as well as the patrons of Riley’s Pub. Most of them, it was clear, came as much for the venue as for Alejandro, to see their pals. If you’ve ever been to the Sons of Herman Hall in Dallas, this feels kind of the same,: a simple elevated stage, a worn wooden dance floor, a bare-bones bar in a room off to the side.

It was kind of great to watch. Not just Escovedo, who was terrific, but the vibe in the room, the old friends clasping each other’s shoulders, women squealing at the sight of familiar faces. Guys who seemed to be as thick as they were tall, human cubes in giant Browns jerseys, beers in both hands, traces of cherry chipotle bbq sauce still on their chins.

As much as anything, I think, they were there to let each other know that they were still around, to support a place that’s old and a little tattered, but standing its ground.. LeBron’s gone. The factories are gone. The Browns are terrible. But it’s not a ghost town yet. And so they drink a lot of beer and make a lot of noise and, until things get better, try to survive by just staying out the way.