Oct. 15

So where were we? Oh yeah, Lowell, Mass., driving by Jack Kerouac’s grave.

I headed north to Vermont from there, nothing more in mind than staring at some fall foliage, watching leaves wither and die for my amusement, the life draining out of them right before my eyes. It’s all about death, autumn in New England, harvest festivals, scarecrows, jack-o-lanterns, plowed-up fields, green things turning bright red and yellow for a fleeting moment and then, inevitably, becoming dried-up, dead and gone. They have a name for it in Vermont, that period after the leaves have gone and before the snows turn things beautiful again. It’s called “stick season.” It’s one of two parts of the year when there aren’t tourists around. The other is in the early spring, when the snow melts, the rains come and the flowers haven’t yet bloomed. They call that “mud season.”

I headed north to Vermont from there, nothing more in mind than staring at some fall foliage, watching leaves wither and die for my amusement, the life draining out of them right before my eyes. It’s all about death, autumn in New England, harvest festivals, scarecrows, jack-o-lanterns, plowed-up fields, green things turning bright red and yellow for a fleeting moment and then, inevitably, becoming dried-up, dead and gone. They have a name for it in Vermont, that period after the leaves have gone and before the snows turn things beautiful again. It’s called “stick season.” It’s one of two parts of the year when there aren’t tourists around. The other is in the early spring, when the snow melts, the rains come and the flowers haven’t yet bloomed. They call that “mud season.”

But it’s not stick season yet. The trees are still full of color, not as flaming bright as some years – there’s been too much rain for the really bright stuff — and it’s just now getting cold. But, muted or not, the mountains are splattered with oranges, reds and yellows, every tree a piece of art, a limited-run performance, open to anyone willing to leave the Interstate.

Which I was. But not until I’d survived a couple of nights in Burlington – one cold overnight spent on a street near the University of Vermont campus, the other spent (courtesy of Couchsurfing.Org) in the home of cellist/novelist/9-11 conspiracy advocate Marc Estrin and his very patient/understanding wife, Donna.

Estrin, like a lot of people in Vermont, is a refugee from the big city, in his case New York, an intellectual who liked the eco-activist, intellectually-open, eccentric-friendly atmosphere and decided to stay. He wears jackets in the house, to keep his carbon footprint small. In addition to his writing (including 5 novels, here’s his website) and his cello performances, he’s a charter member of the Bread and Puppets theater company, an activist (some would say radical) theater group that’s been operating out of the Vermont mountains since the late 1960’s.

Estrin, like a lot of people in Vermont, is a refugee from the big city, in his case New York, an intellectual who liked the eco-activist, intellectually-open, eccentric-friendly atmosphere and decided to stay. He wears jackets in the house, to keep his carbon footprint small. In addition to his writing (including 5 novels, here’s his website) and his cello performances, he’s a charter member of the Bread and Puppets theater company, an activist (some would say radical) theater group that’s been operating out of the Vermont mountains since the late 1960’s.  You know how whenever there’s any kind of anti-corporate political rally, your WTO protests and such, there’s always people in costumes, dressed like ghosts and ogres and carrying giant paper-Mache heads on sticks? If they’re not from Bread and Puppets, then they were certainly inspired by them. This is the group that started turning demonstrations into performance art costume dramas.

You know how whenever there’s any kind of anti-corporate political rally, your WTO protests and such, there’s always people in costumes, dressed like ghosts and ogres and carrying giant paper-Mache heads on sticks? If they’re not from Bread and Puppets, then they were certainly inspired by them. This is the group that started turning demonstrations into performance art costume dramas.

They’ve got a museum, out by Glover, VT., adjacent to their work shop, where lots of their costumes, props, puppets and masks are displayed in an old dusty barn, dimly-lit and, in some places, scary as shit. It’s jammed with menacing figures, death masks, demons. half Mardi Gras, half Hieronymus Bosch. I’ve never dropped acid, mostly because I fear this is exactly the sort of thing my brain would conjure up. In other words, I highly recommend it. Bring a flashlight.

They’ve got a museum, out by Glover, VT., adjacent to their work shop, where lots of their costumes, props, puppets and masks are displayed in an old dusty barn, dimly-lit and, in some places, scary as shit. It’s jammed with menacing figures, death masks, demons. half Mardi Gras, half Hieronymus Bosch. I’ve never dropped acid, mostly because I fear this is exactly the sort of thing my brain would conjure up. In other words, I highly recommend it. Bring a flashlight.

Estrin, for the last few years, has put most of his political energy into his novels and trying to convince whoever will listen (this included me) that 9-11 was not the simple terrorist attack it seemed to be. He’s not claiming to know who did it, he’s just sure that there were controlled implosions and there’s no way the towers could have been taken down by crashing airplanes. His argument mostly, revolves around the mysterious collapse of Building 7, which was adjacent to the Towers, but not hit by a plane. It came down in a way almost identical to the Towers. “Why?,” he asks. “How?”

Estrin, for the last few years, has put most of his political energy into his novels and trying to convince whoever will listen (this included me) that 9-11 was not the simple terrorist attack it seemed to be. He’s not claiming to know who did it, he’s just sure that there were controlled implosions and there’s no way the towers could have been taken down by crashing airplanes. His argument mostly, revolves around the mysterious collapse of Building 7, which was adjacent to the Towers, but not hit by a plane. It came down in a way almost identical to the Towers. “Why?,” he asks. “How?”

I don’t know. I’m just a guy living in a van. He seems like a perfectly reasonable fellow, Marc Estrin does. Maybe he’s right. OK, probably not. The reason most conspiracy theories don’t hold up is because they require a degree of planning, cooperation and secrecy that, in my experience, are nearly impossible to achieve by anyone. Particularly government employees. Oprah could probably pull it off, but I see no evidence she was involved.

But, really, Estrin is what I like about Vermont. It’s a place where the free-thinkers have taken over, where the hippies are kind of in charge. Everybody’s eating granola and installing geo-thermal heaters and generally doing their best to lead their lives without being hassled or hassling anyone else. It’s like Austin with snow.

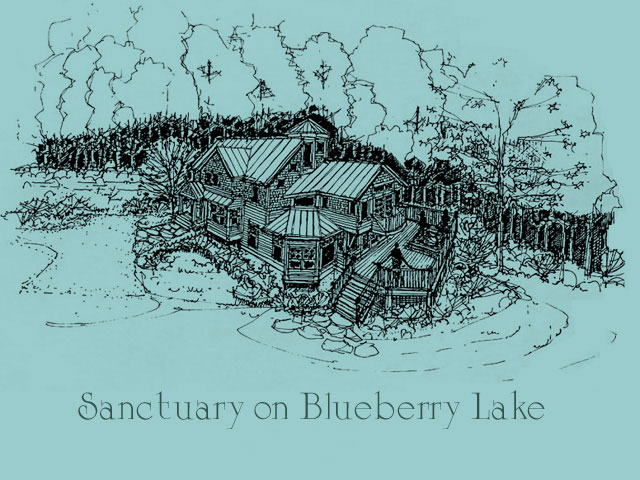

Which is why I should not have been surprised to find the Sanctuary on Blueberry Lake, in the heart of the aptly-named Mad River Valley, where I ended up spending three glorious days in the company of Rita Maranda Brown and her makeshift, ever-changing rock and roll family, a collection of vagabonds and assorted neer do wells that, when I happened to arrive, included (but was not limited to) a reggae band from Boston whose bus had broken down, a “former” pot dealer from Virginia whose father may (or may not) have been law partners with Clark Clifford, and Rita’s main squeeze, Forest George, son of Little Feat legend Lowell George, passionate Deadhead and owner of one of the finest collections of concert posters I have ever seen.

Which is why I should not have been surprised to find the Sanctuary on Blueberry Lake, in the heart of the aptly-named Mad River Valley, where I ended up spending three glorious days in the company of Rita Maranda Brown and her makeshift, ever-changing rock and roll family, a collection of vagabonds and assorted neer do wells that, when I happened to arrive, included (but was not limited to) a reggae band from Boston whose bus had broken down, a “former” pot dealer from Virginia whose father may (or may not) have been law partners with Clark Clifford, and Rita’s main squeeze, Forest George, son of Little Feat legend Lowell George, passionate Deadhead and owner of one of the finest collections of concert posters I have ever seen.

The Sanctuary, most of the time, is a high-end retreat, a bucolic hideaway for paying customers on the far end of a mountain lake, surrounded by woods. The rooms are gorgeous, comfortable, perfect for parties, relaxation, contemplation, whatever you need or want. There are canoes down by the water, fishing poles out on the deck.

The Sanctuary, most of the time, is a high-end retreat, a bucolic hideaway for paying customers on the far end of a mountain lake, surrounded by woods. The rooms are gorgeous, comfortable, perfect for parties, relaxation, contemplation, whatever you need or want. There are canoes down by the water, fishing poles out on the deck.

But on those occasions when paying customers aren’t booked, Rita lets her friends and other vouched-for castaways (the category in which I fall) bunk on the grounds, use the facilities and, generally speaking, have the time of their freeloading life.

So that’s how I end up hanging out with Rita, Forrest, Toft (lead singer of the reggae band, Spiritual Rez) and Todd, the kind of raspy-throated, missing-tooth scraggly philosopher you need in these kinds of situations. “I was born with a silver spoon,” Todd says, “but we had to melt it down.”

Rita, nurturer-in-chief, and 14th-generation direct descendant of Pocahontas (hey, why not?) has been a caterer, an event planner, festival promoter but, more than anything, she has been a music fan who not only loves the music, but the people who make it, to the point that she seeks them out, befriends them, becomes close with them, their wives, girlfriends, children, road crews. She takes them in and they love her for it. She took me in because I’m friends with Joe Nick Patoski, who wrote the definitive Willie Nelson biography, and Rita has spent many hours on the road with Willie and Family.

But her first love has always been Little Feat, which is how she met Todd – another hardcore Little Feat aficionado and, of course, Forrest George., who is sweet and enthusiastic, like a puppy, really, but also troubled by some of the demons that killed his dad. He’s recovering now and needs a safe place and loving arms to help him through. That would be Rita.

They snap at each other a lot – the puppy thing again – but clearly love each other enough to forgive transgressions almost immediately. She protects him, chides him, pretty much does everything short of whapping him across the snout with a rolled-up newspaper. And he adores her. How could he not?

So this is the household I entered and from the moment I arrived, felt a part of. Toft, young and bright and often shirtless on stage, was writing a new song on the living room couch. Todd was on the laptop, monitoring Little Feat message boards and occasionally uttering proclamations like, “Everybody’s so busy asking questions, they can’t hear the answers.” Exactly.

We listened to music. We ate wonderful meals. We smoked cigars and other things. (Did I mention there was a reggae band involved?) We drank beer. We drove into town for milk and cigarettes and more tequila. We hung out on the deck, marveling at the mountains and the water and serenity of it all. We watched Little Feat videos. Forrest kept pulling out more concert posters from the basement, jacked up at the sight of each one, as if he’d forgotten how cool they were.

“Rita! Rita! Rita!,” he would say. “Look at this one. Look at this one.”

They were all still there when I left, including the members of Spiritual Rez, who declared this “the best breakdown we’ve ever had” and a few more friends and musicians who wandered in. For breakfast, the last day I was there, everyone had French toast with ice cream on top. Rita made the French toast.

She also made sure we straightened up our rooms and cleaned the kitchen, making sure things were neat and orderly for the customers arriving that afternoon. We were happy to do it. It was the least we could do for Rita, who’d done such a fine job of taking care of us all. Sanctuary in the Mad River Valley. Yes.