So where we? Oh yeah, Lafayette, La., grooving to the blues brunch at the Blue Dog Cafe.

It started getting cold in Lafayette, 29 degrees overnight. In other words: time to go. I headed west towards Houston, where I foolishly applied for a newspaper job several years ago, but was told the editor decided not to hire me because he felt “disrespected by your pants.”(This is true.) In retrospect, wearing the Bart Simpson “Eat My Shorts” boxers over my jeans was a bad workplace choice. Lesson learned.

In spite of this, I still like Houston. Funky Houston. Not the strip-mall-no-zoning-mattress-stores-on-every corner Houston. Not the big-glass buildings-filled-with-oil-executives-and-money-launderers Houston. And certainly not anytime-between-May-and-October Houston, when the whole place is pretty much a mosquito-infested steam bath. But Funky Houston. Weird Houston. It’s there. It’s just that, unlike Austin, they don’t advertise it.

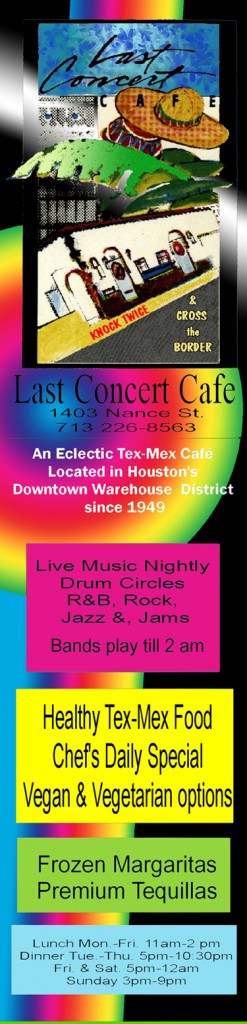

There is, for instance, the Last Concert Cafe, tucked up under I-10 on Nance Street, hidden back among the warehouses and (regrettably) ever-growing-loft communities on the edge of downtown. There is no sign. And the red front door is always locked. You have to knock twice to get in. Not that they’re hiding anything, or would ever not open the door. But it’s the principle of the thing. And it keeps away the oil executives, who don’t like having to ask for permission to do anything, even walk into a funky restaurant.

There is, for instance, the Last Concert Cafe, tucked up under I-10 on Nance Street, hidden back among the warehouses and (regrettably) ever-growing-loft communities on the edge of downtown. There is no sign. And the red front door is always locked. You have to knock twice to get in. Not that they’re hiding anything, or would ever not open the door. But it’s the principle of the thing. And it keeps away the oil executives, who don’t like having to ask for permission to do anything, even walk into a funky restaurant.

They’ve got Shiner on tap, a fine assortment of Mexican items, cool artwork on the walls and a Pepto Bismol pink paint job on the interior walls that is oddly soothing, much like actual Pepto Bismo. The menu’s gotten nicer since the last time I was there, the items a little pricier. I don’t care. It’s still the Last Concert Cafe.

So there’s beer and enchiladas and tequila but, most importantly, Monday night is Open Mic Night at the Last Concert Cafe, which is a short-story/one-act-play title just waiting to be used. There’s a big old patio behind the restaurant, a corrugated tin roof, propane heaters when needed and, on Monday nights, an endless parade of sideshowrefugees and charming misfits with almost no musical skills of any kind. But they climb up on that stage, emoting till their veins are about to burst, singing thee songs they’ve written about fishing boats and broken hearts and why they can’t get a job. And, really, it’s kind of wonderful. A little scary, but wonderful.

You wander out there, with your beverage , find an unoccupied metal chair (there will be more than enough) and take it all in, the guy who looks like a Cossack Hell’s Angel, with a skullcap and leatherwear (including a low-hanging codpouch), a long gray braided ponytail and black eyebrows that curve up and out like a handlebar moustache. If Rasputin rode Harley, this is how he’d look.

There’s Red-Eyed Carl, kind of a droopy guy in a wrinkled short-sleeve shirt, strumming a guitar he clearly cannot play and singing his heart about things I couldn’t make out. And a thrash band that may or may not have been called Saturnine. The lead singer’s dad, all decked out in a poncho and a guitar clearly left over from his days in a Dio cover band, shredded while his boy wailed. And some guy yells out from the front table, “I didn’t know Clint Eastwood played with the Jonas Brothers.”

That guy, it turns out, was J. Frederick Rhetoric, who I’d noticed as soon as I walked in because he was pulling heaavily on a joint and looking around furtively, like a 2nd-grader who just got caught eating a booger. I thought, to be honest, that he had a mild case of Down’s Syndrome. His eyes were a little vacant. He kept them pointed mostly towards the floor, except when the music kicked in and he started head-banging so hard I thought his neck would break.

But then J. Frederick, after informing the emcee that he’d like to be introduced as “Whitey” took the stage with a guitar of his own and proceeded to do a mostly-awful round of jokes with occasional musical stings. The jokes were groan-inducing, bad puns, juvenile punchlines and lots of painful silence. But he expected that. He liked it. It seemed to be part of the act. I didn’t know whether to be proud of him or feel sorry for him. He looked like Jim Gaffigan with brain damage and I think there was an Andy Kaufman performance art vibe about the whole thing.

And not all the jokes were terrible. One of them – “I’ve been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder. But don’t worry. They’re sending me to a concentration camp.” – was kind of brilliant. J. Frederick’s regular job is as a deejay at a strip club. It really is. When he was onstage, he seemed alert, aware and pretty sharp, if not terribly funny. And then, when he walked out of the spotlight, his head went back down and his eyes went blank and it was as if someone had turned off his brain switch. I still down’t know what to think.

But if I were back in Houston on a Monday night, I’d sure as hell go back.