So where were we? Oh yeah, Houston, whining about the Final Four.

So where were we? Oh yeah, Houston, whining about the Final Four.

I’ve been kind of cranky lately, even more than usual. This is not necessarily a bad thing, since it keeps salespeople and small children at a distance. No one ever tries to sell me band candy or vacation homes.

But there are downsides to being cranky all the damned time. For one thing, It increases the likelihood that baristas will spit in your latte. In a nice fern-shaped pattern, sure, but still, it’s not good.

I’ve felt my surliness quotient going up for the last week or so and it finally occurred to me that it was rising in direct proportion to the proximity of my hometown. The closer I get to Shreveport, the surlier I become.

We have a difficult history, Shreveport and me. I hated growing up there. It was too hot, too dull and way too southern for my tastes. I spent pretty much my entire childhood just waiting for the day I could get the hell out of there, which I did within months of graduating from high school. I hated Shreveport so much that Peoria, yes Peoria, seemed like a paradise . And, for me, it was. For a while, anyway, until I realized — slowly — that just because people didn’t have southern accents, they weren’t necessarily smarter or more tolerant. I grew up assuming that if I could just get north of Little Rock, everyone would be liberal. But that was before I realized that the Midwest is filled with all-white small towns, culturally isolated and in a lot of ways, less forgiving than any place in the south. Pekin High School’s athletic teams were called The Chinks. And the first time I heard someone with a flat, neutral midwestern accent use the word, “nigger,” I was devastated. I thought I’d escaped all that. I was incredibly naive.

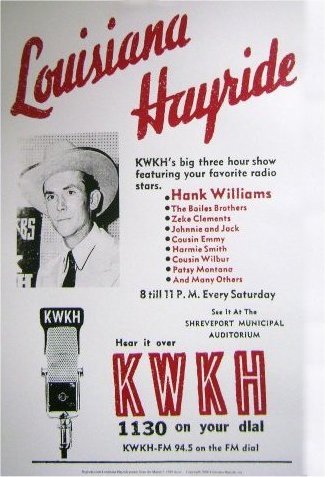

But not necessarily wrong about Shreveport, the capital of redneck north Louisiana, a place with corrupt and racist cops, dominated by right-wing fundamentalist churches, mostly Baptist. Shitkicker central. There were other, cooler things going on, but I didn’t really appreciate them at the time. There was a vibrant soul/R&B recording studio, Paula Records, a great black radio station, KOKA and of course there was the Louisiana Hayride, which is where Elvis and Johnny Cash and Hank Williams hit it big when they were considered too outrageous for the Grand Ole Opry. The announcer, Frank Page, lived right across the street from me and was hanging out with those guys all the time. I didn’t understand that, of course. The Hayride, to me, was just redneck music. One more thing to escape.

It took a while, but as the years passed, I grew more understanding of the place — of the music, of the food, the cultural quirks. I wasn’t proud to be from there, necessarily, but I didn’t hate it anymore. They had drive-through daiquiris, for God’s sakes. It would have been way worse to grow up in Pekin.

And then, in 1992, i stirred it all up again, on the occasion of my 20th high school reunion. School integration – real school integration, not the token crap the district had tried to get away with until the federal courts told them to knock it off – came to Shreveport in 1970, my sophomore year at Captain Shreve High School. The students from all-black Eden Gardens High School (which became a junior high) were bussed into Captain Shreve, which had only been open for a couple of years.

There was outrage, but mostly from the parents, who screamed at school board meetings and opened up white-flight academies, mostly at those Baptist churches I mentioned earlier. There were some fights in the hallways, but for the most part the students just went to class and got on with it. There wasn’t a lot of social mixing. The high school cafeteria was as segregated as a 1950’s lunch counter. The black kids sat on one side. The white kids on the other.

But – and this is key – the one place where we mixed completely was in the gym. I was the basketball team manager and the gym was a place where black kids and white kids hung out, played against each other, became friends. If practice went too long and the black players missed the bus, we took them home. We went on road trips together. We stayed in hotels together. We made fun of each other, acted like idiots in the locker room, bitched about the coaches. We were a team.

And being part of that was, without a doubt, the single best thing about my high school experience. Because I was the manager, I had a key to the gym and a desk in the locker room that became my office. The gym was my little universe. I used to mop the floors, unasked, on nights before games – pissing off the girls’ volleyball coach who’d marked off her courts with masking tape. I was on constant patrol for people walking on the tile floor (yes, it was tile and therefore a terrible, hard, slippery surface) in street shoes. I was ruthless when it came to protecting my gym, my floor, my world.

And I loved that it wasn’t a segregated world. That it belonged to the black athletes – Donald Webb, Edwin Scott, Johnny White, Carlos Pennywell – every bit as much as the white athletes. It was the first place in my southern life where I’d had meaningful, extended contact with African-American peers. It was important.

Which is why I was so disturbed when I heard that our 10th high school reunion was being held at an all-white country club and that there were two reunion committees, one black and one white, planning reunions on two separate weekends, making it virtually impossible to attend both. I had friends on the “white” committee who swore to me – and I believed them – that it wasn’t done on purpose, that the committees had formed independently of each other and just couldn’t coordinate their events. It was unfortunate but not intentional. Just one of those things.. So I went to that reunion, at that all-white country club, with none of my black classmates anywhere to be found. And I had a pretty good time. There was tequila.

But then, 10 years later in 1992. It happened again. In exactly the same way. This time made me angry, because I knew it wasn’t merely an oversight. They KNEW about the other “black” reunion committee. They had to have known that having the event again at the all-white country club guaranteed that no black alumni would come. So, there was no chance that I would run into Donald Webb or Barry Kimble or Patsy Williams, people I’d wondered about but hadn’t stayed in touch with. I felt cheated. I thought it was wrong.

So I made a big, public stink. I called a friend at Newsweek who wrote about it. The story got picked up in the local paper, with op-eds written by other classmates who accused me of manufacturing controversy where none existed. Their point – and for them, I’m sure it was true –the reality of their high school lives was that black and white students had run in very different circles and no one should be surprised that the reunions reflected that.

We ended up, believe it or not, on the Maury Povich Show, representatives of the “black” reunion committee on one side, the “white” committee on the other and me in the middle, getting lambasted by both. Jackie Harris, head of the black committee, made a point of introducing herself to me on camera, because she’d never met me in high school. She was as angry as the white organizers – Ricky Murov and Richard Hiller, both of whom had been friends of mine.

Povich, of course, wanted as much confrontation as possible, wanted it to be about hatred and discrimination. He’d have loved it if the white kids had shown up wearing robes and burning crosses. But that was never my point. Murov and Hiller aren’t racists. They weren’t then and they aren’t now. This wasn’t about white people going out of their way to discriminate against black people. It was about people not being able to see beyond their own experience.

The black kids on that panel and the white kids on that panel remembered high school years where they had almost no contact with anyone from another race, where their dealings with each other were laced with mistrust. Why should they want to have a reunion with people they didn’t even know?

But their experience wasn’t mine. I interacted with black students every day, not just guys on the basketball team, but in class, and after school. I wanted to see those people again. That’s what this was about: how people tend to assume that their world is THE world. It’s not malice. It’s short-sightedness. That’s what I wanted to talk about. That’s why I was angry.

We never discussed any of that, of course. Povich went off on some tangent that I can’t even remember. Murov and Hiller got all indignant that they were being called racist when they weren’t. Jackie Harris resented this guy she’d never met questioning her motives. It went badly.

Until Barry Kimble, one of our classmates, came on stage. He was an African-American football player, one of those guys I wish I could have seen at the reunion. He was always a nice guy, affable, smart. He continues to be all of those things.

He’d never been on television before but he came out and talked, calmly, clearly and movingly about how he has kids that go to Captain Shreve, how it would never occur to them to have segregated reunions and how we shouldn’t have them, either. It was time for all that to be behind us. We were the generation where everything changed. And the reunions should reflect that.

Cue the applause, Maury nodding his head as if he’s actually been listening. Me, off to the side now, relieved.

There have been reunions since then, although I haven’t been invited. Lots of people in Shreveport are still angry at me. They think I made them out to look like racist rubes, that I’d gone all Hollywood liberal and had lost touch with my roots. Yeah, maybe.

So Shreveport always makes me nervous, all that teenage “fight or flight” anxiety comes bubbling up. I get surly.

But my friend David Egan – a white classmate who remained my friend even after the brouhaha – was playing a gig in downtown Shreveport, at Chicky’s Boom Boom Room & Oyster House on Texas Street. I’m not sure why he took that particular gig, since it’s not the kind of joint he usually plays. He’s a Grammy-nominated artist, for God’s sake, a guy who writes and plays with Irma Thomas. But, hey, a gig is a gig.

He knew right away that it wasn’t his crowd. The p.a. was blaring generic dance music, thump-thumping Rihanna and Beyonce. Everyone appeared to in their 20’s, guys dressed like golfers, women in spangled blouses and keel-over heels. One girl, already loud and drunk before she came in, wanted to know why she couldn’t get free admission on her birthday. The cover was $5.

I sat at the bar and took it all in. David, pro that he is, rolled out as many Professor Longhair and Doctor John songs as it took to keep their attention, which he got. They swayed with him, they danced to him. He won them over.

And I started to notice something. This was not just an all-white frat-boy crowd. There were black guys at the bar, in dreads. There were lesbian couples. There were jocks and hippies, gays and straights. At a bar in downtown Shreveport. This is not how it used to be.

And when David’s set ended, and the thumping dance beats recommenced, the crowd that moved on to the dance floor was a sight to see. There were clumps of guys, dancing together. There were white guys dancing with black girls. Black guys dancing with white girls. Gay couples. Straight couples. Nobody-seems-to-care couples. I was stunned, impressed. And moved. Really moved.

And when David’s set ended, and the thumping dance beats recommenced, the crowd that moved on to the dance floor was a sight to see. There were clumps of guys, dancing together. There were white guys dancing with black girls. Black guys dancing with white girls. Gay couples. Straight couples. Nobody-seems-to-care couples. I was stunned, impressed. And moved. Really moved.

I never thought I’d see a crowd like that in Shreveport, La., especially not at a downtown bar called Chicky’s Boom Boom Room. The guys dancing together weren’t necessarily gay, some of them surely weren’t. The black girls and the white girls had arrived together. That they were dancing together in one room was no big deal to them. But it was to me.

It was the way I’d always wanted Shreveport to be. I watched them, I kid you not, for hours, just smiling to myself. I did not cry. But I could have. And by the time I went to bed, at 5 a.m., I wasn’t feeling surly at all.