So, where were we? Oh yeah, Chicago, being perused by the Secret Service.

I had chores to do after that – the emptying of sewer tanks, the repair of various battery accessories in the Traipsemobile, the drinking of even more beer. There were friends to see in Indiana and Ohio, a weird October blizzard to avoid in western Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, return-visit promises to be kept in Boston and New York.

The weeks flew by, not so much in a blur, but as if I were in an alternate time-space continuum, a Traipsathon bubble separate from the rest of the world. I’d found a way to live in a perpetual autumn, a universe where the leaves were always at the peak of their colors, where the temperatures were always in the 60’s or maybe the 70’s, where nothing heavier than a sweater was ever required. It was never too hot and never too cold. And I’d been in this world since July , as I made my way north from Seattle through the Yukon and on to Alaska. And it stayed with me through August and September and October and into November, as I slowly wandered south and east, a step ahead of winter everywhere I went.

It has completely screwed up my perception of time, this constant movement from one fall day to the next. Because I wake up in the same bed every morning, surrounded by all the same stuff, there’s a “Groundhog Day” sense to my life, and not in a bad way. But it compresses time and distance. Edmonton feels like it was yesterday. So does Minneapolis. And Chicago. And Cincinnati. The grass was green, the trees were full of color, the beer was delicious. Whenever anyone mentions a place, my immediate response is always, “I was just there!.” Except, when I think about it, it’s actually been months since I was Canada, almost a year since I’ve been in Texas. When was I in Colorado? Or Arizona? Wasn’t I just in L.A.? No, my friends all tell me, you’ve been gone a lot longer than you think.

It has completely screwed up my perception of time, this constant movement from one fall day to the next. Because I wake up in the same bed every morning, surrounded by all the same stuff, there’s a “Groundhog Day” sense to my life, and not in a bad way. But it compresses time and distance. Edmonton feels like it was yesterday. So does Minneapolis. And Chicago. And Cincinnati. The grass was green, the trees were full of color, the beer was delicious. Whenever anyone mentions a place, my immediate response is always, “I was just there!.” Except, when I think about it, it’s actually been months since I was Canada, almost a year since I’ve been in Texas. When was I in Colorado? Or Arizona? Wasn’t I just in L.A.? No, my friends all tell me, you’ve been gone a lot longer than you think.

Part of this, clearly, can be explained by the fact that I’ve been drunk a great deal of the time. I never really had routines when I lived in one place. But I do when I’m on the road. I find the local coffee shop. I find the local Anytime Fitness. I find the local pub. There’s a rhythm to my life that it’s never had before. And – on those rare occasions when I stay in a motel or someone else’s home – I can feel the disruption of my routine. When I don’t wake up in the parking lot of some strange bar in some strange town, I feel disoriented. It’s a glitch in the Matrix. The bubble is momentarily gone.

It’s not that I don’t know where I am. Or that the places don’t seem different. I spent Halloween in Scranton and Thanksgiving in Atlanta, Christmas in Miami and New Year’s Eve in Key West. I watched the World Series in Cincinnati and the BCS Championship in Orlando. It’s not like I wake up in the morning and go, “Holy shit, is this Charleston or Charlotte?” Okay, yes, I did that once. But, in my defense, those are very similar names.

So, as I drifted from Chicago to Indianapolis to Louisville to Cincinnati to Cleveland to Scranton and beyond, I often felt like I was a kind of alien explorer, passing unnoticed through all these places where people were going about their daily lives – going to the supermarket, sneaking out of the office early, hurrying to the high school football game – while I observed them from some other dimension. Tomorrow, I thought, they’ll be doing the same things, barely cognizant of all those other similar worlds, the ones in Whitehorse and LaCrosse and Framingham. And, tomorrow, I’ll be gone. Another day, another planet, another perfectly indistinguishable autumn day.

I take a weird sort of comfort in this, the similarities between the coffee shops and the Anytime Fitnesses and the pubs. The ones in North Dakota don’t seem all that different from the ones in Massachusetts or Maryland or South Carolina. This, I realize, is self-selection, like tuning into the NPR station in whatever town I happen to be. But, the thing is, there always IS an NPR station. And a funky locally-owned coffee shop with a goofy name that makes it seem like it was meant just for me (Lookout Joe in Cincinnati, Fat Cat Pie Company in Norwalk, The Muddy Waters Coffee Bar in Charleston, The House of Joe in Melbourne, FL and , my favorite, The Drunken Monkey Coffee Bar in Orlando) And there’s always a pub with chatty regulars, “the best wings you’ve ever had” and an IPA on tap, brewed someplace nearby. (Neon’s Unplugged in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine, Mickey Gannon’s off Drinker Street in Scranton, The Federal Lounge in Durham, The Trappeze Pub in Athens, GA, The Pour House in Charleston and Redlight, Redlight in Orlando). Every town is interesting, at least to me, and proud of its quirks. They want you to try their lobster rolls or their crabcakes or their cheesy grits. They want you to appreciate that they make their own scones or their own barbecue sauce. They want you to know they exist. They are, generally speaking, pleased to have a stranger wander into their town. It’s reassuring, I guess, proof that they are connected to the outside world, to places they’ve never heard of and will likely never see.

I take a weird sort of comfort in this, the similarities between the coffee shops and the Anytime Fitnesses and the pubs. The ones in North Dakota don’t seem all that different from the ones in Massachusetts or Maryland or South Carolina. This, I realize, is self-selection, like tuning into the NPR station in whatever town I happen to be. But, the thing is, there always IS an NPR station. And a funky locally-owned coffee shop with a goofy name that makes it seem like it was meant just for me (Lookout Joe in Cincinnati, Fat Cat Pie Company in Norwalk, The Muddy Waters Coffee Bar in Charleston, The House of Joe in Melbourne, FL and , my favorite, The Drunken Monkey Coffee Bar in Orlando) And there’s always a pub with chatty regulars, “the best wings you’ve ever had” and an IPA on tap, brewed someplace nearby. (Neon’s Unplugged in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine, Mickey Gannon’s off Drinker Street in Scranton, The Federal Lounge in Durham, The Trappeze Pub in Athens, GA, The Pour House in Charleston and Redlight, Redlight in Orlando). Every town is interesting, at least to me, and proud of its quirks. They want you to try their lobster rolls or their crabcakes or their cheesy grits. They want you to appreciate that they make their own scones or their own barbecue sauce. They want you to know they exist. They are, generally speaking, pleased to have a stranger wander into their town. It’s reassuring, I guess, proof that they are connected to the outside world, to places they’ve never heard of and will likely never see.

There have been times when I’ve felt the rhythm turning into a rut, a sense that, even though I’m seeing different places, I’m doing too much of the same thing. Some of this, I’m sure, is the inevitable post-Alaska letdown, the lack of a short-term destination goal. Going from Athens to Charleston to Charlotte can’t help but feel a little less exciting than going from Whitehorse to Banff. Next year, when I drive to Panama, I’m sure I’ll warmly reminisce about that stretch when my days seemed so easy to predict.

In mid-November, close to my 57th birthday, I was having more than my share of stuck-in-a-rut days. I was, once again, flirting with the onset of winter, the days getting grayer and cooler, but not quite cold enough to send me scurrying south. I visited friends in Bethesda, in Silver Springs, in Baltimore and northern Virginia. I drank coffee, I drank beer, I went from one Anytime Fitness location to another. The Beltway was my home.

The Anytime Fitness gyms, where I shower and usually do a little workout, are generally reliable places where I can ride a stationary bike, do a little yoga and, most of the time pretty much have the place to myself. The showers are usually private and available. It’s like having my very own spa.

But the one in Rockville, Maryland was filled to overflowing, people waiting in line for access to machines and only one stationary bike, a reclining model at that. And even that one was broken. Every time I tried to adjust the seat, I ended up with my knees in my chest. After 20 minutes of trying to fix the damn thing, I just gave up. I’d have just showered and left, but the bathrooms were all occupied.

But the one in Rockville, Maryland was filled to overflowing, people waiting in line for access to machines and only one stationary bike, a reclining model at that. And even that one was broken. Every time I tried to adjust the seat, I ended up with my knees in my chest. After 20 minutes of trying to fix the damn thing, I just gave up. I’d have just showered and left, but the bathrooms were all occupied.

So, even though it was after dark, later than I usually work out, I drove half an hour south on the Rockville Pike to the next-closest Anytime Fitness, in Kensington, Maryland. It was in a nicer area than most of the Anytime locations, which tend to be in strip malls next to AutoZones and Dollar Stores. This one was in a wooded area, next to a church, around the corner from a house with a white picket fence.

I worked out. I showered. I took my time. It was nearly 9 p.m. by the time I left the building and headed back towards the Traipsemobile, which I’d parked at the church next door. If the day had gone differently, if the Rockville gym had been less crowded or if I’d decided it was too late to work out and just gone straight to a pub, I wouldn’t have been there when I was.

And I wouldn’t have encountered the elderly Asian woman who was walking towards the Traipsemobile as I left the gym. There wasn’t anyone else on the street. I nodded at her and, expected she’d ignore me as I got into the Traipsemobile and drove way, once again anonymous and on the move.

Instead, she called out, “Do you know the way to the police station?” I told her that I didn’t, that I was just passing through town.

“I can’t get my son to answer his phone,” she said. “ I need to find the police.”

She was insistent and, I finally figured out, was asking me for a ride. She was tiny, but not fragile. Elderly but not unsteady. And my first thought, I’m ashamed to admit, was that she might be running some sort of scam.

She was insistent and, I finally figured out, was asking me for a ride. She was tiny, but not fragile. Elderly but not unsteady. And my first thought, I’m ashamed to admit, was that she might be running some sort of scam.

But the more we talked, the more I understood that she was really, legitimately frightened. Her story was confusing and asking about the details didn’t seem to help. Her son was supposed to pick her up? Where did he live? Did she think something had happened to him? Was there an accident? Where did she live? Why did she need the police again? Just because he wasn’t answering his phone?

It took me a while, longer than it should have, to figure out she was suffering from dementia. She kept repeating parts of her story, asking the same question over and over again. “Why would he leave me like this? Why? WHY?” And then she’d say, “I still have all of my marbles. They don’t think so, but I do.”

She told me her fragmented story as we drove around, as I tried to use Yelp and my GPS system to find the nearest police station, which turned out to be way harder than I expected. The nearest sub-station had, apparently, been shut down due to budget cuts. It took three phone calls and several baffling circuits of the City Hall parking lot to figure this out. The nearest open law enforcement entity was the Montgomery County Police Station in Glenmont, two towns and 20 minutes away. So that’s where we went.

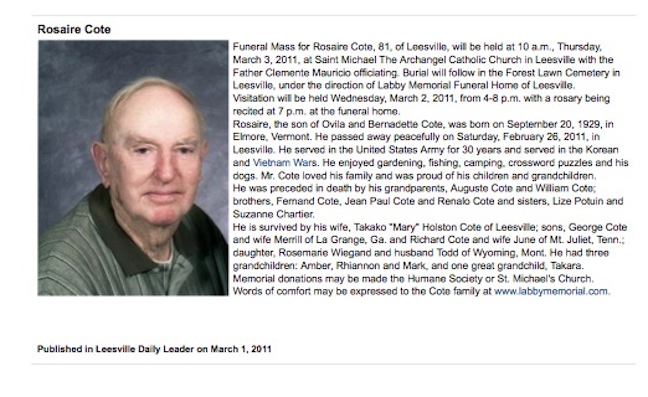

Her name, she said, was Mary. The more she talked, the more confused she seemed. But her anger and frustration were real. And parts of her story, remembrances of her early life, rang true. Here’s the story Mary told me.

She was born in China in 1930 , of Japanese parents who were killed during the second Sino-Japanese war that preceded World War II. Orphaned, she was sent to Japan, to be raised by relatives who didn’t really want her. It sounded like a terrible life.

She married a U.S.. serviceman after the war and returned with him to the U.S., to Leesville, La, where they raised a son together. 20 years ago, Mary’s husband died. She was a widowed war bride, a foreigner in a southern town. That also sounded like a terrible life.

But it wasn’t, she said. She had friends. And a garden. And a house she loved. She remarried just 5 years ago, to man in whom she had no romantic interest, but who treated her kindly. And then, last year, he died, too.

This is where the story gets harder to believe. Mary said that her son, married and living in Maryland, invited her up to visit for a few weeks after the funeral, a little vacation, a quiet place to grieve.

This is where the story gets harder to believe. Mary said that her son, married and living in Maryland, invited her up to visit for a few weeks after the funeral, a little vacation, a quiet place to grieve.

But instead, with no warning, he’d put her in this place that was like a prison, with locks on the doors and filled with people who, she said, were nothing like her. “They sit around all day. They do nothing. There is nothing to do. It’s like they are already dead.”

“I call my son, to ask him why he has put me in this place. Why? I cannot stay there. This is no way to live. I just want to go back to my home. Why?”

She wanted the police to find her son, not because she thought he was missing or in danger, but because she wanted him to explain what he’d done. If he wouldn’t answer his phone for her, he surely couldn’t hide from the police. She was going to get to the bottom of this. She was going to find out why.

She told the story over and over again, adding new details, but never changing the basic facts. Her real name, she said, was Takako, but Americans could never remember that, so everyone called her Mary. And her son, she said, was an orphan, too. She’d found him abandoned in Japan but had never told him. I’m not sure why, but I believed that part, too.

She wasn’t sure how long she’d been in this prison where he’d left her, with the attendants who watched her and the old people who seemed half-dead. But she noticed how the security system worked. That if one door opened, the alarms went off at every door. She waited for someone to accidentally open the front door, which everyone could see, and go there to shut off the alarm. When they did, Takako sneaked out the the back. She escaped.

And then she ran into me, on a dark street around the corner from a house with a white picket fence.

We finally found the police station and waited for nearly an hour while the duty officer sorted things out. Takako had a number for her no-good son and her Louisiana driver’s license, long since expired.

Eventually, a little after 11 p.m., the attendants arrived from the Arden Courts of Kensington, an assisted living center specializing in Alzheimer’s and Memory Loss. It’ a half block from the Anytime Fitness. Takako hadn’t walked very far.

They assured me that her son visited her quite often, at least twice a week. She’d been there for six months and, most of the time, seemed content. But sometimes she’d get angry and demand to know why they were keeping her prisoner.

“Don’t take me back there,” she said. “I don’t want to go back.”

“Mary, it’ll be fine,” the attendant said. “Everybody’s been worried about you.”

I let them take her. What else could I do? The attendants seemed friendly and compassionate. There was no indication that she was being ignored or abused. There was nowhere else for her to go.

So I walked with her out to the Arden Care van. Before she got in, she pulled me down to whisper in my ear. “Come check on me,” she said.

And I did. I went back three days later and tried to see her. But they told me that “Mary” was taking a nap. I didn’t want to wake her. I left her some cookies and a flashlight, in case she went on another unauthorized late-night walk. There were photocopied signs above every entrance warning that one of the patients was an escape risk and to please be careful entering and exiting the building. They were playing “Walking On Sunshine” on the public address system as I left.

I drove south from there, into Virginia and North Carolina. My perpetual autumn continued. For Takako, though, winter was closing in.